One of the most frequently repeated beliefs about the Parminter cousins is that they based the design of A la Ronde on the chapel of San Vitale at Ravenna, which they are said to have seen on their travels around Europe. In favour of this idea, San Vitale is octagonal in shape, with an octagonal dome above, and is also highly decorated inside with extensive picture mosaics on biblical and Roman Imperial subjects.

One of the most frequently repeated beliefs about the Parminter cousins is that they based the design of A la Ronde on the chapel of San Vitale at Ravenna, which they are said to have seen on their travels around Europe. In favour of this idea, San Vitale is octagonal in shape, with an octagonal dome above, and is also highly decorated inside with extensive picture mosaics on biblical and Roman Imperial subjects.A relationship between San Vitale and A la Ronde is relied upon to confirm that the women not only went on a Grand Tour, which was in effect a holiday lasting around eleven years, and also to identify that holiday and its associated classical historical experiences as the major influence upon and motive force driving their activities for the remainder of their lives.

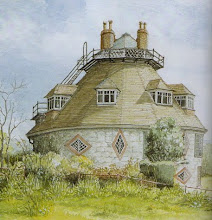

Octagonal buildings are not uncommon worldwide, and notable examples include the Tower of the Winds in Athens which dates from 50 BCE, the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem which was completed in 691 AD, and the Nott Memorial. Neither did Jane and Mary Parminter have to leave the British Isles to see eight-sided churches. The Unitarian Octagon Chapel in Norwich was completed in 1756, when Jane was six years of age. By 1767, the Bath Octagon Chapel had opened and within a very short time had become so fashionable that visiting families would book a pew at the same time as renting a house for the season. Popular amongst Scottish Presbyterians and English non-conformists, John Wesley actively encouraged Methodists to build octagonal chapels, and between 1761 and 1776 at least fourteen were constructed, of which a few survive. In keeping with Enlightenment and Reformation thinking, octagons are egalitarian and modern, allowing congregations to experience a space that reflects a system of belief that rejects high and low, front and back, priest and supplicant. Octagonal houses dating back to the early eighteenth century include a large cottage on Uplyme Road in Lyme Regis (picture below), and the Dutch Cottage at Rayleigh in Essex.

The octagon was known to be an easier shape to thatch than a traditional cottage, and by popular European superstition devils and spirits could hide in a room with right-angled corners. American phrenologist and designer Orson Squire Fowler led a fashion for octagonal homes in mid-nineteenth century Canada and the North Eastern USA. According to Fowler, an octagon house was cheaper to build, provided additional living space, received more natural light, was easier to heat, and was cooler in the summer. These benefits all derive from the geometry of an octagon, as the shape encloses space efficiently, minimizing external surface area and consequently heat loss and gain, and also reducing building costs. A circle is the most efficient shape, but difficult to build and awkward to furnish, so an octagon is a sensible approximation. Victorian builders were used to building forty-five degree corners, as in the typical bay window, and could easily adapt to an octagonal plan.

The octagon was known to be an easier shape to thatch than a traditional cottage, and by popular European superstition devils and spirits could hide in a room with right-angled corners. American phrenologist and designer Orson Squire Fowler led a fashion for octagonal homes in mid-nineteenth century Canada and the North Eastern USA. According to Fowler, an octagon house was cheaper to build, provided additional living space, received more natural light, was easier to heat, and was cooler in the summer. These benefits all derive from the geometry of an octagon, as the shape encloses space efficiently, minimizing external surface area and consequently heat loss and gain, and also reducing building costs. A circle is the most efficient shape, but difficult to build and awkward to furnish, so an octagon is a sensible approximation. Victorian builders were used to building forty-five degree corners, as in the typical bay window, and could easily adapt to an octagonal plan.As many 18th century non-conformist Christians adopted eight-sided buildings, some sub-denominations developed unique architectural forms. The Moravian Brethren had similar beliefs and doctrines to those attributed to Martin Luther around a hundred years before Luther’s declaration, and had travelled from middle Europe through Britain and on to Massachusetts and Canada, carrying with them a tradition of “leichen kappelchen”, or Corpse Houses. Corpse Houses allowed the dead to be laid out before burial in places where the cold climate made it impossible at certain times of the year to dig a grave, and from the late eighteenth century until the mid nineteenth century many of them were octagonal in shape. It is possible that the Moravian Brethren appreciated the octagon’s ability to maintain a more consistent internal temperature, and also possible that the choice of shape was connected with ecumenical and spiritual equality, that in death as in life all sisters and brothers are equal before God. 18th century Brethren may also have shared common beliefs about evil forces in corners, and concerning the spirits of the dead, that may have made the octagon an attractive overall solution.

A la Ronde is not eight-sided, but sixteen-sided. Sixteen-sided buildings are much less common, probably because they are more difficult to build, but sixteen sides more closely approximates a circle. A la Ronde, a French phrase most closely associated with dancing in a ring, was named by Jane and Mary Parminter when the house was built, and the name might reasonably be expected to have been chosen based on the owners’ ideas and intentions inherent in its design. It is perhaps surprising if the cousins were so motivated by their experience of the chapel at Ravenna that the name makes no explicit or implicit reference to this influence (for example, Little Ravenna, or Il Capelli), the building itself is only as similar externally to San Vitale as it is to over a dozen other polygonal buildings, and in fact less so than the Bath and Norwich Octagons, and there are no known pictures or souvenirs at the house to commemorate the visit to Ravenna notwithstanding its alleged significance. The house name is French, not Italian, and seems more likely to be intended to evoke the women’s dynamic use of the house, moving around it in a circle every day according to the light. It should also be considered whether the Parminters, as non-conformist Christians, were likely to have devoted themselves so completely to the celebration of a Roman Catholic place of worship, without very much more experience of it than a casual visit on an excessively long holiday.

Advocates of a link to San Vitale also point to parallels in the internal décor. San Vitale has been decorated using small, evenly sized mosaic tiles to create vast pictorial studies of Old and New Testament events and of significant figures in the Holy Roman Empire (see example picture above). It is difficult to see how this is sufficiently similar to the Parminter’s use of found natural materials in abstract and secular collages to be able to draw this conclusion. It is as similar or dissimilar as any other decoratively tiled interior. More likely influences on the decorative style at A la Ronde would probably include the summer houses and grottoes built in the grounds of large country houses in the early 18th century in response to the fashion for rocaille, or rococo. Jane and Mary Parminter would no doubt have been aware of Bystock, a couple of miles away, which had a well-known octagonal summer house in the grounds, paved with 23,000 sheep’s hooves. There are striking similarities between the Shell Gallery and Scott’s Grotto at Ware in Hertfordshire, which was built and decorated in the 1760’s by Quaker poet John Scott, using shells, flints and coloured glass. And in this period, featherwork interiors were fashionable and commonplace.

Advocates of a link to San Vitale also point to parallels in the internal décor. San Vitale has been decorated using small, evenly sized mosaic tiles to create vast pictorial studies of Old and New Testament events and of significant figures in the Holy Roman Empire (see example picture above). It is difficult to see how this is sufficiently similar to the Parminter’s use of found natural materials in abstract and secular collages to be able to draw this conclusion. It is as similar or dissimilar as any other decoratively tiled interior. More likely influences on the decorative style at A la Ronde would probably include the summer houses and grottoes built in the grounds of large country houses in the early 18th century in response to the fashion for rocaille, or rococo. Jane and Mary Parminter would no doubt have been aware of Bystock, a couple of miles away, which had a well-known octagonal summer house in the grounds, paved with 23,000 sheep’s hooves. There are striking similarities between the Shell Gallery and Scott’s Grotto at Ware in Hertfordshire, which was built and decorated in the 1760’s by Quaker poet John Scott, using shells, flints and coloured glass. And in this period, featherwork interiors were fashionable and commonplace. The closest matched structure for shape and size – almost exactly to the inch – is George Washington’s design for a 16-sided treading barn. Is it possible that they or someone they knew had seen it? Is there a connection to American non-conformists farming in Pennsylvania in the late 1700’s? On this, more later.

The closest matched structure for shape and size – almost exactly to the inch – is George Washington’s design for a 16-sided treading barn. Is it possible that they or someone they knew had seen it? Is there a connection to American non-conformists farming in Pennsylvania in the late 1700’s? On this, more later.